An aluminum billet is a semi-finished, solid bar of aluminium with controlled internal structure and geometry, produced for downstream forming or machining. In contrast the plain term aluminum refers to the metal in any of its many commercial forms, from raw ingots and castings to sheet, plate, foil, powder and finished components. For engineers and buyers, the practical difference is this: when tight mechanical properties, predictable grain structure, low internal porosity and high machining accuracy matter, choose billet; when bulk storage, remelting or low-cost cast parts are acceptable, generic aluminium ingot, scrap or casting-grade metal may be the right starting point.

What people mean when they say “aluminum”

The word “aluminum” by itself is broad. In commerce and engineering it can mean elemental aluminium metal, a class of aluminium alloys, a cast ingot, a slab, plate, sheet, or a finished component. Context decides whether the speaker means raw material for remelting, semi-finished stock, or the alloy used in an application. When you read technical documents, check whether the text uses the term “ingot”, “billet”, “bloom”, or “slab”, because those are standard industry categories with distinct shapes and downstream uses.

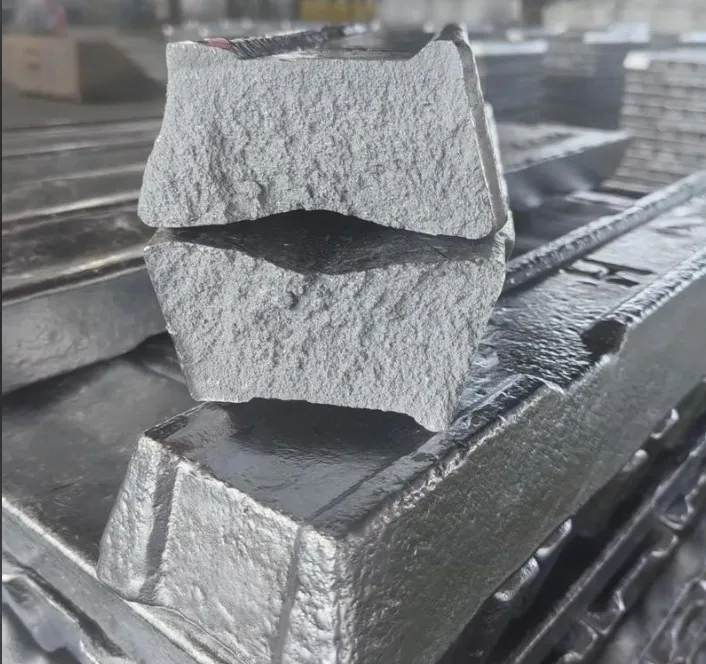

What is an aluminum billet?

A billet is a semi-finished metal product with a round or square cross-section and a limited cross-sectional area. In aluminium production, billets serve as feedstock for extrusion, CNC machining, forging, or further rolling. Billets are typically produced by continuous casting or by hot-working an ingot or bloom into a controlled bar form. The hallmark features are consistent chemistry, refined internal microstructure, low porosity and minimal inclusions, which lead to reproducible mechanical performance during downstream processing.

How billets are produced: principal processes

There are several routes to make aluminium billets. Each route influences the billet’s internal structure and cost.

-

Direct chill (DC) continuous casting

Molten aluminium is cast into a water-cooled mould while the emerging bar is steadily withdrawn and sprayed with water for controlled solidification. DC billets usually show good cleanliness and are the most common feedstock for extrusion and forging. -

Homogenized cast billets

After casting, billets undergo a homogenization heat treatment that reduces microsegregation and equalizes alloying element distribution. This step improves extrudability and final mechanical properties for heat-treatable alloys. -

Hot-rolled billets from ingots

Large ingots can be hot-rolled or hot-worked into billet-sized bars; this route can refine grains and close casting porosity, though processing cost is higher. -

Extrusion billet production and forging billet production

Extrusion billets are usually long cylindrical logs sized by diameter and length. Forging billets tend to be shorter, heavier blocks optimized for press or hammer work. Both types demand precise chemistry and heat treatment control.

Metallurgical reasons billets differ from generic aluminium castings

The superior performance that billets often exhibit is rooted in metallurgy and process control:

-

Grain structure control: controlled solidification and homogenization produce uniform grains that machine and deform predictably.

-

Lower porosity and fewer inclusions: careful melting, filtration and casting reduce gas entrapment and non-metallic particles that compromise strength and fatigue life.

-

Consistent alloy chemistry: production spec limits for billets are stricter, which helps tight tolerances in mechanical output.

-

Heat treatment compatibility: billets for heat-treatable alloys are cast and homogenized for stable response to solution treatment and ageing.

These microstructural advantages explain why parts machined from billet often survive higher loads and longer fatigue life than equivalent cast parts.

Clear comparison: billet vs ingot vs cast component vs slab

| Aspect | Billet | Ingot | Cast component | Slab / Plate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical form | Round or square bar | Rectangular block, tapered | Near-net shape, complex geometry | Wide flat block for rolling |

| Production method | DC casting, extrusion casting, hot-work | Simple casting moulds | Sand, die or permanent mould casting | Continuous casting or slab mills |

| Primary use | Extrusion, forging, CNC machining | Storage, remelt feedstock | Final or semi-finished parts | Rolling to sheet/plate |

| Internal cleanliness | High | Variable | Variable, often higher porosity | Moderate to high |

| Mechanical repeatability | High | Low to moderate | Variable, often lower than billet | Moderate |

| Typical industries | Aerospace, automotive, high-precision engineering | Aluminium smelters, foundries | Consumer goods, housings, engine blocks | Shipbuilding, heavy plates |

(See the procurement table below for alloy-specific notes.)

Typical alloys used for billets and why alloy matters

Billet production uses a broad range of aluminium alloys. Choice depends on the desired balance of strength, corrosion resistance, weldability and formability.

-

2xxx series (e.g., 2024, 2219): high strength and fatigue resistance for aerospace structural applications, but limited weldability.

-

5xxx series (e.g., 5052, 5083): non-heat-treatable marine-grade alloys with excellent corrosion resistance and weldability.

-

6xxx series (e.g., 6061, 6063): versatile heat-treatable alloys that balance strength, extrudability and weldability; very common for extrusion billets.

-

7xxx series (e.g., 7075, 7050): very high-strength alloys used in aircraft and high-performance applications; require careful casting and homogenization.

Billet producers often offer a range of chemistries, and buyers must specify alloy series and temper because downstream processing and final properties depend heavily on alloy selection and heat treatment.

Mechanical properties, inspection and specification points

When you receive billets, inspect and test for:

-

Chemical composition report (mill certificate) confirming alloying elements and limits.

-

Grain structure and inclusion inspection via micrograph or NDT methods for critical parts.

-

Porosity and cleanliness tested with appropriate metallurgical analysis when fatigue-critical use is intended.

-

Dimensional tolerances and straightness for extrusion billets so feeding and die alignment remain stable.

A common procurement practice is to require a full mill test certificate (MTC) and to add acceptance criteria for ultrasonic testing or radiographic inspection for high-stress parts.

Table: typical procurement checklist for a billet purchase

| Buyer requirement | Typical specification or acceptance method |

|---|---|

| Alloy and temper | Specify alloy number and temper (for example 6061-T6 or 7075-T651) |

| Chemical certificate | Mill test certificate showing composition and trace element limits |

| Heat treatment | Homogenization details and recommended solution/ageing cycles |

| Geometry | Diameter, length, straightness tolerances |

| Mechanical tests | Tensile test values, elongation, yield strength (if needed) |

| Cleanliness | NDT or metallographic sample acceptance criteria |

| Traceability | Heat number and cast date linked to certificate |

| Surface condition | Scale removal, skin thickness limits if extruding |

Why engineers choose billets for critical components

Three practical reasons often drive the choice:

-

Predictable mechanical performance

Controlled casting and homogenization mean designers can rely on published tensile and fatigue values with smaller safety margins. -

Precision machining and surface finish

Billets machine cleanly and allow closer tolerances, reducing finishing cost. -

Forming reliability

For extrusion or forging, billets produce consistent flow through dies or presses, leading to fewer defects in the final part.

Cost, lead time and sustainability trade-offs

Billets command higher unit price than generic ingot or remelted castings because of tighter process control and added steps (homogenization, inspection). However total part cost may be lower when billet feedstock reduces scrap, rework and rejects in machining or forming. Buyers should weigh raw-material savings against machining allowances, cycle time, and the value of improved performance.

From an environmental viewpoint, aluminium recycling remains highly efficient. Billets commonly include secondary feedstock, and producing parts from billet often reduces total lifecycle waste through longer part life and better recyclability at end of life.

Manufacturing roadmaps: when to specify billet in a drawing or purchase order

If your component must meet any of the following, specify billet:

-

High fatigue requirement or cyclic loading

-

Tight dimensional tolerances beyond typical cast part capability

-

High-strength alloy (2xxx or 7xxx series) that must be homogenized prior to forming

-

Deep internal machining where porosity would be catastrophic

In a purchase order, include alloy, temper, homogenization, mill certificate requirement, dimensional tolerances, and any agreed NDT or micrograph acceptance criteria.

Practical examples of applications that prefer billets

-

Aerospace structural fittings and machined components (landing gear fittings, control linkages).

-

High-performance automotive components and custom wheel blanks.

-

Precision tooling, jigs and fixtures that require tight tolerances and repeatable material behavior.

-

Specialized extrusions where billet cleanliness ensures defect-free profiles at high extrusion speeds.

Table: quick rules of thumb for choosing feedstock

| Need | Prefer | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest material unit price | Ingot or remelt | Accept lower consistency |

| High repeatability in machining | Billet | Controlled microstructure |

| Complex cast shapes with low mechanical demand | Casting | Minimal machining required |

| Large flat products | Slab or plate | Produced by rolling mills |

How billet terminology is used differently in practice

In marketing or aftermarket language, “billet” sometimes simply means “not-cast” or “machined from solid” even when the product began life as bar stock rather than a dedicated billet. For procurement and engineering clarity, avoid marketing terms and specify the real technical attributes required. Industry standards and mill certificates provide the true traceable details buyers need.

Sample specification snippet you can copy into an RFQ

Supply aluminium extrusion billets, alloy 6061, production route DC cast and homogenized, diameter 200 mm nominal, length 6,000 mm, mill test certificate required showing chemical composition and tensile values, straightness tolerance 2 mm per 6 m, ultrasonic inspection optional at buyer request.

Use the exact alloy and temper codes recognized in standards rather than the word “aluminum” alone.

Table: common alloy families and typical billet uses

| Alloy family | Typical billet uses | Key property emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| 1xxx (pure aluminium) | Electrical, chemical containers | Electrical conductivity, corrosion resistance |

| 2xxx | Aircraft structural parts | High strength, fatigue resistance |

| 5xxx | Marine extrusions and welded structures | Corrosion resistance, weldability |

| 6xxx | General extrusions and frames | Balanced strength, extrudability |

| 7xxx | Highly stressed aerospace parts | Very high strength, careful processing required |

FAQs

Aluminum Billet vs. Casting: Performance & Supply FAQ

1. Is an aluminum billet stronger than a cast part?

2. Can you make high-quality billets from recycled aluminum?

3. What is the typical shape and size of a billet?

4. Does “billet part” mean it was machined from a single block?

5. Are billets used only for extrusion?

6. How does the price of billet compare to aluminum ingots?

7. What documentation should I expect with a billet shipment?

At a minimum, you should receive a Mill Test Certificate (MTC). For aerospace or critical automotive parts, look for:

– Ultrasonic inspection results (for internal cracks)

– Grain size verification

– Homogenization cycle records

8. Do all aluminum alloys handle extrusion equally well?

9. Is machining from billet more economical than using castings?

10. Can I melt down a billet and recast it into a different shape?

Closing recommendations for buyers and engineers

-

Use precise language in drawings and purchase orders: specify alloy number, temper, homogenization requirement and testing obligations rather than the word “aluminum” alone.

-

For fatigue-critical or high-precision parts, insist on billets with documented homogenization and a mill test certificate.

-

For cost-sensitive, bulk remelt applications, ingots or lower-grade castings remain appropriate. Balance raw material cost against post-processing and part lifecycle performance.